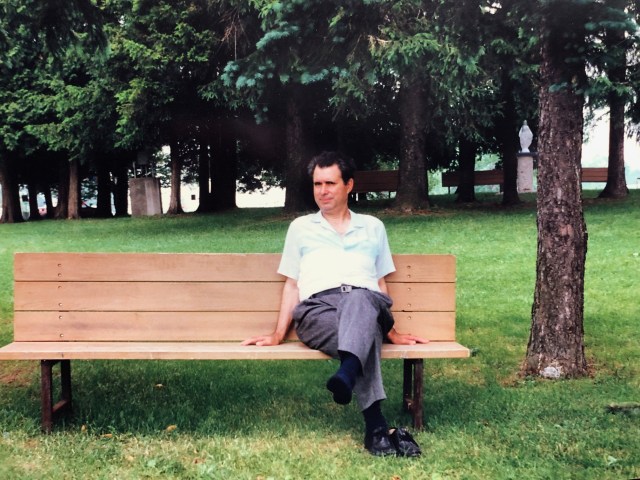

My father, Antonio Cabral de Melo at Mary Lake, June 17, 1990

My father, Antonio Cabral de Melo at Mary Lake, June 17, 1990

“Tell me about your father.”

So writes Anthony de Sa at the end of More than a King, his Substack essay about his complicated relationship with his father. In a stripped bare confessional of the heart wounded, seeking healing, de Sa shares his father’s flaws as well as his redeeming virtues with his readers and invites them to share their own stories with him.

I admire his honesty, his resolve to see his father, not through revisionist nostalgia, but through the shadows and light which reveals a full human being.

It’s a coincidence that, like de Sa, I also wrote about my father on a November day. My text was inspired by reading José Luís Peixoto’s “Morreste-me”, his own love letter to his father.

Perhaps it’s the commemoration of All Souls’ month that conjures up the memories of our dead fathers and a need to reclaim them through our writing; to restore justice to their name, their goodness even while acknowleding their flaws.

I share my text written in both Portuguese and English, in memory of my father’s journey from the Azores to North America and to the life he made possible for me because of his emmigration.

I thank Anthony de Sa and José Luís Peixoto for their writing on a difficult theme.

I hope many sons and daughters will find some threads of their own family truths and perhaps a path forward to healing their own wounded hearts.

What I should have told my father before he died: A Reflection on loss and redemption: a leaving (Azores) and an arrival (Canada)

My father, now that you are gone forever, I feel your absence; now that you have left us for more time than I thought possible, I miss you.

While you were alive, I was never able to understand you. I hid myself from you and you were never able to find me after the day you emigrated when I was still a mere child. On that day, you disappeared from my life and, being little, I didn’t understand the reason why; all I knew is that you had left me alone with my mother: you had abandoned me. How was I, a child, to understand why you had to emigrate? There were reasons which only the adults knew and could understand. My mother told me, after I woke up without you by my side, that you had gone and, my world of childhood crumbled in disillusion. You didn’t tell me goodbye, you simply vanished.

And when you returned, after a long absence of three years, I was older; no longer the six year old boy you left behind; I was now nine years old. I had not seen you for so long that you appeared like a stranger returning from a faraway place, and instead of welcoming you back, I kept my distance. A few months later, you brought me and my mother to Canada. But only six weeks after arriving in our new country, my mother received a letter to inform her that my grandmother was very ill and needed her daughter. Very quickly plans were made for me and my mother to return to São Miguel. I was heartbroken. I had spent three years without a father and now I was being taken away from you again. I know that you cried inconsolably watching us leave but in my mind it felt like abandonment all over again. By the time my mother and I returned to Canada three months later, it felt like it was too late for you and for me, and I just couldn’t forgive you for the perceived betrayal of letting me go for a second time. I rejected you and could not look into your fatherly eyes.

It was only when I turned sixteen that I was able to make some peace with you. Still, during all the time that I grew up and became a man, I never understood that you were right there by my side; that you had returned after your three year absence. I imagined it as if you had never returned at all because the child in me had never forgiven your absence: the child that I was believed that he had lost his father forever. It is only now, five years after your death; five year without your presence, that I start to see the truth about what happened on that fateful day when you left. I believed that you didn’t love me because you hadn’t even said goodbye. But I had never known your side of the story.

Recently, I asked my mother to explain what happened on the day you left. She told me how you embraced me and cried over me, while I still slept. You didn’t want to let go of me, on that morning that changed my life forever. Yet I thought that you had abandoned me by choice. If only I had seen your tears and felt the warmth of your tight embrace, perhaps then I could have understood and forgiven your leaving; but it wasn’t so, and you paid a heavy price for that act of emigration. You lost your son who did not understand how you could have just disappeared from his life.

Now that you aren’t with us, I want to tell you that I miss you, that I now see that you had never really abandoned me; that you loved me. I kept myself emotionally distant from you because I never got over that experience of you leaving me without showing me your sorrow in having to go away. The child inside of me believed that he had lost his father, but like a good father, you remained by my side, watching me in silence, resigned to pay the price for a crime which you had not committed: the crime of abandoning your son.

I want to thank you for all that you did for me. Had you not come to Canada, how different my life would have been back there on our island of São Miguel. You brought me to a land where I was able to have a life full of comfort and opportunities and all of it because of your sacrifice. Forgive me for not recognizing what you did for me while you were with us; forgive me my foolish impression that you had stopped loving me. I now see that you never abandoned me but, sadly, I distanced myself emotionally from you for most of my life based on a misunderstanding.

Your illness, however, brought me to you in ways that nothing else had before. When you got sick with cancer, it was me who you wanted to take you to all those tedious doctor’s appointments, each one bringing less and less hope that you would survive. I sat with you for countless hours in Princess Margaret Hospital, waiting in silence; you never complained or showed fear about your future. You sat there reading your Portuguese newspapers as if everything was normal.

When the therapy stopped working and there was no further hope of your recovery, in those last months when you lay on the sofa, unable to walk, I came to see you often. I sat with you and you smiled warmly and it brought me comfort. You became like a helpless child and I helped you get dressed, I held a urinal container in my hand while you held on to me so that you would not fall; when you no longer had the strength to get up, I wheeled you into the bedroom. You were always quiet and never complained.

Once, in the middle of the night, my mother called for help while I slept in the next room. You had soiled yourself and she needed help in cleaning you. We undressed you together in silence. I removed your grey undershirt, soaked at the back. I looked down on your naked body, helplessly flat on the bed, unable to move. It killed me to see you so vulnerable. I watched my mother try to make you comfortable but your face betrayed a pain you would not speak so that she would not worry about you.

I hated having to do your chores. It should have been you taking care of your recycling and garbage night. I didn’t want to shovel your driveway or your front steps, I didn’t want to do your grocery shopping; I didn’t want to plan my life around your dying. I was angry at having to watch you die. The hurt was infinitesimal. It was tied up with my feeling for you all my life; our silences, our differences. I didn’t even know who I was to you. Do you love me? I remember thinking as I looked at your fading body. And all the doubts of my childhood came back to haunt me, confusing my adult mind once again.

You then took for the worst during Holy Week and we prepared for your imminent dying. The doctor gave me the brochure to read so that I’d know the stages of death. But you did not die that quickly. On Good Friday you became conscious again and lucid of mind. You called everyone to come and say goodbye. On Easter Sunday, I held you from behind while the homecare worker washed you. When she left, I was alone with you for a few moments. You asked me to bring you the statue of O Senhor Santo Cristo from the dresser. You held it in your hands and you kissed the Suffering Christ; and I heard you whisper your remarkable prayer: Dai-me a Vossa Graça. (Give me your grace). This was your only prayer in your time of need. And I still remember it today as a testament to your deep and simple faith. This was to be your last day at home.

The next day, I had to accompany you by ambulance to Grace Hospital where you were to die a few weeks later. We went alone; you and I, in that ambulance passing the streets you would never walk or see again. My knees were shaken as they wheeled the stretcher into the room where you would spend your last days. For the remaining weeks that you lingered, I came every morning on my way to work to feed you. Sometimes you were aware of me. Once you gave me a big happy smile. On the last days, you kept your eyes closed while I fed you porridge. I don’t think you felt pain. You were resigned with your death the way that you were resigned to your life’s joys and disappointments; the joy of having two granddaughter’s that my brother gave you; the disappointment that I didn’t.

When we received the late night call to say that the time had come, we rushed to be with you. I watched your breathing become shallower and shallower until you took your last breath. It felt unreal to watch you, the man who was my father, die as simply and quietly as you had lived your life: without fuss.

It’s been five years since that day you died. I am still trying to recover from the loss of you. I had lived my life with the belief, false as it was that you didn’t really love me. The impressionable young boy that I was misunderstood your leaving. But as much as I may have reserved my judgment on your love for me and my love for you, in the end, I think we lived that love, not through words but through the quiet actions and silences of a lifetime, especially those of your last years.

In my mind, I now return to that fateful morning when you left the island. I close my eyes and think of you again. I am six years old and you haven’t left. Now I can smile.

O que eu devia ter dito ao meu pai antes de ele morrer

Pai, agora que aqui já não estás, sinto a tua ausência; agora que já te foste embora, sinto a tua falta.

Enquanto eras vivo, nunca te compreendi. Escondi-me de ti e nunca mais me encontraste a partir do dia em que emigraste, quando eu era apenas uma criança de seis anos. Um dia, desapareceste e eu não entendi a razão; apenas sabia que me tinhas deixado sozinho com a minha mãe. Tinhas-me abandonado.

Como podia eu compreender que tinhas de emigrar por motivos que só os adultos sabiam? A minha mãe disse-me, depois de eu acordar sem ti ao meu lado, que te tinhas ido embora, e o meu mundo de criança desfez-se em desilusão. Não me disseste adeus, apenas desapareceste.

E quando regressastes, três anos depois da tua ausência, eu já não tinha seis mas nove anos, e em vez de te abraçar de novo, nunca te perdoei a traição da tua partida clandestina.

E quando me trouxeste para o Canadá, rejeitei-te, e nem olhava para os teus olhos de pai amoroso. Fiquei homem e durante esse tempo todo nunca cheguei a compreender que o meu pai estava ali, perto de mim, que tinhas voltado. Era como se deveras nunca tivestes regressado. A criança que eu era nunca perdoou a tua ausência. A criança que eu era perdeu o seu pai para sempre.

É só agora, depois de teres morrido, depois de cinco anos sem a tua presença que começo a compreender a verdade. Pensava que nunca tinhas gostado de mim, por isso me deixaste. Mas não sabia a tua história.

Foram as palavras da minha mãe que me fizeram compreender. Contou-me como me abraçaste e choraste naquela manhã em que eu dormia e tu me dizias adeus e não me querias deixar, naquela manhã que mudou a minha vida para sempre, quando pensei que me tinhas deixado por abandono e não por necessidade.

Se, pelo menos, tivesse visto as tuas lágrimas, se tivesse sentido os teus abraços, talvez tivesse perdoado a tua partida. Mas não foi assim e pagaste o preço desta emigração. Perdeste o teu filho que não sabia, que não percebia como foi que tu pudeste ausentar-te de mim.

E agora que já não estás conosco, quero dizer que sinto a tua falta, que soube tarde demais que não me tinhas abandonado, que me amavas. Perdoa o teu filho que ficou sempre criança, como no dia em que partiste e pensava que me tinhas abandonado.

Tinha um pai como muitos não têm e não compreendia. Agora, agora já é tarde, mas quero dizer-te:

Obrigado por tudo o que fizeste por mim. Se não tivesses vindo para o Canadá, como teria sido a minha vida na nossa ilha de São Miguel? Trouxeste-me para um país onde pude ter uma vida cheia de conforto e oportunidade, e tudo por causa do teu sacrifício.

Desculpa-me nunca ter apreciado o que fizeste. Desculpa-me a minha impressão de que não me amavas. A criança que eu era pensou que perdeu o seu pai, mas como bom pai, estiveste sempre ao meu lado, vigiando-me em silêncio, resignado a pagar por um crime que não cometeste, o crime de abandonar o seu filho.

E o seu filho, sempre à espera do pai que se fora embora, agora é que vê que voltaste, mas só agora, depois de tantos anos, é que reconhece que não me tinhas abandonado.

Pai, agora que já não estás entre nós, penso em ti e sinto a tua falta. Afinal de contas não foste tu que me abandonaste, fui eu que te abandonei.

Fecho os meus olhos de novo e penso em ti, tenho ainda seis anos e não partiste para o estrangeiro. Agora posso sorrir.

Inspirado pela leitura do livro Morreste-me de José Luís Peixoto

Also posted in Filamentos (artes e letras)

Dearest Emanuel, My heart aches for the little boy in Sao Miguel whose father abandoned him. What a heavy burden for that little one to carry and to live with. As children, we do not understand our parents’ burdens, worries and fears. Those are rarely shared with us in an attempt to protect us from the hard things in life. My father gave a warning: Don’t tell all you know. It was told to me many times over. I didn’t know why. Only much later, after my father’s death did I discover the motivation for that instruction. I understood and with the understanding came compassion and love.

I hope you have a measure of peace in the relationship with your father and that you can truly feel compassion, understanding and love between the two of you.

Thank you for sharing such intimate thoughts about your relationship with your father. I am deeply moved.

With my love,

Carol

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Carol, thank you so much for your words and for sharing you own story. Emanuel

LikeLike

Dear Emanuel,

Upon re-reading my words, I realize I should have said,” who thought his father abandoned him.” Sorry for that omission. I am glad that you know now, you were loved and treasured by your father.

Peace and love,

Carol

LikeLiked by 1 person