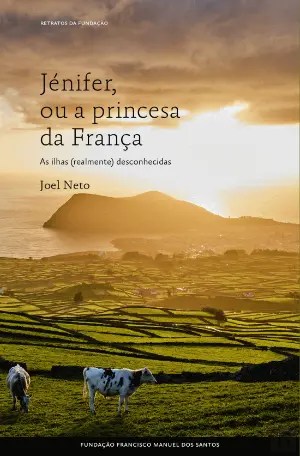

Joel Neto’s Jénifer, ou a Princesa da França, As ilhas (realmente) desconhecidas translated into English by Diniz Borges and Katharine F. Baker, as Jénifer, or a French Princess, The (Truly) Unknown Islands,” published by Letras Lavadas, has been nominated for the 44th annual Northern California Book Awards 2025. It’s the first book of fiction by an Azorean writer to be nominated for this prize. The reading of this book inspired me to write the following text:

An Uncomfortable Truth of a (Truly) Unknown Paradise

If I hear one more person tell me how delighted they are to be going to the Azores on holiday I’ll, proverbially, scream! In the last few years, the discovery of the magical beauty of the Azorean islands, now unshrouded of its mythical aura through thousands of posts on Instagram, Facebook and Travel blogs, has stirred a desire in the average tourist, Portuguese descendant or not, to make a trip, minimally, to São Miguel, the largest of the archipelago’s nine islands of the Azores. An outcome of this influx of tourism has been an increased demand for accommodation, in its traditional form of hotels and small pensions, and as of recent times, through the offering of Airbnbs not only in the city of Ponta Delgada but even in small towns and villages.

I should be thrilled that after spending my youth trying to convince my Canadian friends that the Azores was a real place, everyone now looks at me with a sort of envy – how lucky is Emanuel for having roots there! But back in the 1970s and 1980s, even those in cosmopolitan Toronto had not heard much about these “exotic” islands, lost somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

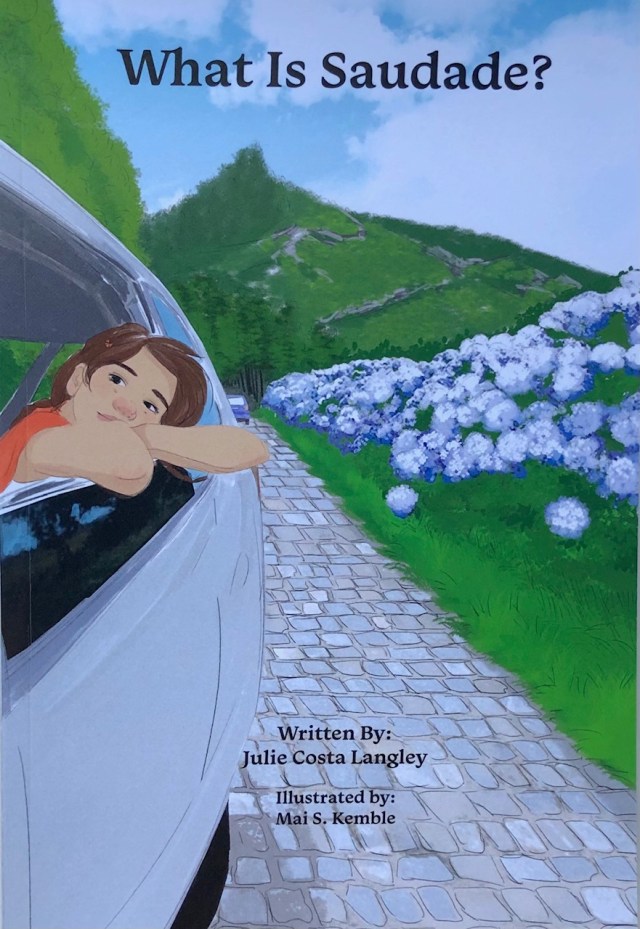

I should be happy to finally have the saudade I felt for most of my life for my home of origin validated and celebrated by the countless social media posts and “likes” that affirm the beautiful landscapes of Furnas, Sete Cidades, and other places of interest throughout these beloved islands.

But the truth is that the mystery and novelty of coming from such a treasured part of the planet, special as it may be, no longer allows me to remain in a perpetual state of mythical saudade for a geographical home. It did, for a long time, but I worked out my feelings of ambivalence over my family’s immigration to Canada and in later life, through many visits to São Miguel over the last twenty years to both my home town of Ponta Delgada as well as my father’s village of Achada in Nordeste. The familiarity of spending time with both the land and the family members who still live on the island shed away the fantasy of longing for the home of my childhood.

All this preamble is to demonstrate that I most assuredly would not be open to write a reflection on the theme of poverty or of any of the other social ills many who live on the islands face, if I was still under the spell of saudade. The danger of this state of mind and heart is that it sees the world through a rose-tinted glass. It’s like the curation of the best Instagram posts to promote a world that, beautiful as it shows, is also plagued by serious social challenges. The pretty photos on “Insta” divert our attention – first generation immigrants and luso descendants alike – and make us feel good and proud to belong to these islands, even if the Portuguese language is no longer part of everyone’s heritage.

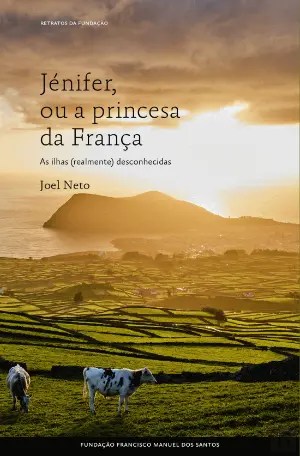

It is with this personal current state of awareness that I was receptive to reading Joel Neto’s novella, Jénifer, or a French Princess: The (Truly) Unknown Islands, translated by Diniz Borges and Katharine F. Baker from the Portuguese, Jénifer, ou a Princesa da Franca: As Ilhas (Realmente) Desconhecidas.

The author inserts himself in the story, reporting documentary-style, to reveal a side of Azorean island life few wish to acknowledge: the persistent presence of poverty in all its disturbing and uncomfortable truth set against a backdrop of breathtaking geographical beauty.

In his raw yet compassionate look at lives ruined or unsustainable due to economic want, resulting in systemic and generational poverty, Joel Neto follows the life of Jénifer Armelim, a young girl of almost eleven, who sits on the stone wall across from her housing project, rather than go to school. Jénifer dreams of being a French Princess. She was told by an aunt that she had genealogical connections with the French, based on her surname; but I think this is her way of imagining a way out, of getting up from the wall that keeps her nowhere. Jénifer also wants to be a unicorn when she grows up or an astronaut or a whaler. In other words, she’s dreaming big of a way out of her confined life of poverty on a small island.

The French Princess ideal could be a substitute for the American Dream so many Azoreans have followed for generations. It’s a looking forward to a place that will bring opportunity, wealth, status, a place in the world. If nothing else, a new car and a house to call one’s own.

Certainly, when the wave of Azorean immigrants came in the thousands to the USA and Canada in the 1960s or earlier, as did my family, they hoped for a better life and for the majority, thankfully, they found it. But the conditions and opportunities for those willing to work any job were to be found in North America, and moving up the economic ladder was a real reward, whether you were educated or not.

In fact, education from a people whose highest academic achievement was mostly the quarta classe was not pursued well into the future generations of immigrant children. Our parents focused on work and saving and buying a home. My father worked in construction, on a tobacco farm, and at Neilson’s Chocolate factory until his retirement. My mother went to work in clothing and toy factories, as did my paternal grandmother and my two aunts on my father’s side.

The immigrant children either attended school or dropped out, usually to work. It made sense to these early immigrant families fleeing the clutches of poverty or close to it, to pursue economic success. If you could make a living off the trades, then why waste time getting a university or college education? One of the faults of the statistical findings in Ontario over the years is the persistent belief that the Portuguese did not participate in higher education. Perhaps many did not, but the alternative was still a productive membership in society, through work. In my close family circle of first cousins, all of them completed some form of higher education. In my case, I dropped out of high school near the beginning of grade nine. Like Jénifer, I learned to skip school from grade 6 until I formally abandoned school. The reasons in my case had to do with my mal-adaption to coming to Canada and it wasn’t until my late teenage years that I found a way back into formal education. But at sixteen, I told my parents that I did not want to stay in school so the only other option my father allowed me to pursue was work. And work I did. My first job was on an assembly line and later I worked for Eaton’s, a major department store in Toronto. I learned the value of money and saving up, all before I was formally educated with a high school upgrade, a college diploma in Accounting, and ultimately a university degree. I mention this because if my parents could not force me to pursue education while I was in my early teens, they guided me to the next best thing, and luckily, the education followed.

However, most of the western world, Canada and the USA included, is now very different from 60 years ago and the opportunities for new Azorean immigrants of today are more challenging that in the past.

I have a young cousin who left her family in São Miguel with the dream of making her life in Canada because there are limited opportunities for her back in the Azores. But she will face the problem of an exorbitant rental market in Toronto and, without any work experience and only a High School diploma, I wonder how soon the dream will become a sour reality. For her sake, I hope she makes it. I have known her most of her life, seen her every time I have gone back to visit family in Achada, a small village in Nordeste, where my father’s family comes from and where some still reside. It is very strange to meet her on my own turf in the city of Toronto. Seeing her for the first time here, I was reminded of my own immigration to Canada.

I was nine years old then, when I came to Toronto with my parents in 1968. We were the last of our immediate family to leave Ponta Delgada, the city where I was born. My father’s family, his parents, and his two sisters with their children had already left. On my mother’s side, her brother went to Fall River, Massachusetts, USA. My father first went to stay with family in New Bedford before going to Toronto to be with his parents and sisters, saving enough money to later bring my mother and me.

Our family left the Azores for a better life and, I am glad to report, that they did find it. Through hard work and persistence, they provided for their children and gave them the opportunity for a life better than they would ever had, had they stayed on the island.

None of us was poor before immigration but we were not rich either. However, growing up in the Azores, I knew that poverty existed, albeit on the fringes of my modest yet comfortable life in the city of Ponta Delgada. My mother used to volunteer once a week with a charitable organization to hand out milk and bread to children who lived in the neighbourhood of the Bairros Novos, so close to where we lived on Caminho da Levada. I knew of it but I was sheltered from it, and certainly did not visit it as a child.

Yet, poverty was all around me, I realize now, but it wasn’t spoken about. It was acknowledged, at least by my maternal grandmother who would take in a poor neighbour and offer her a free lunch, or give away a pair of shoes received in a container from relatives in New Bedford or somewhere in California. My mother remembered that once in a while a shipment of clothes and other items would arrive from the land of abundance, and everything was gratefully received and shared.

If we were not officially poor, why did we leave? Why did so many relatives on my father’s side leave their lives in Achada for lives in New Bedford, Massachusetts or Toronto in Canada? On my mother’s side, to Fall River, Massachusetts, Sacramento, California, and even Bermuda.

In my parents’ case, my father had owed more money than he could ever repay and the only solution to be solvent was to emigrate. He managed to pay off all of his debt before saving enough money to buy a house here in Toronto. Back home, my father had a grocery store. He gave credit to everyone, I suspect because many could not pay. But their inability to pay resulted in his insolvency.

I know that money problems had been very much on my father’s mind when he dared write a letter to António de Oliveira Salazar , believing that Portugal’s president of the Estado Novo would miraculously come to the rescue of those citizens in need. I don’t blame my father for his naiveté because when I was growing up, I had learned in school that we could, and should, trust our leader as a benign father figure who cares for his children.

My father had left his home in the countryside as a young boy of fourteen and came to work in the city, Ponta Delgada. That was his opportunity for economic change. His parents owned some land, vineyards and had their own house, a house that now would be the dream of a thousand tourists who would love to have a view by the ocean but which my eldest cousin, who inherited it, holds on to it as part of our family heritage. It’s where I stay when I visit Achada and soak up the views of the Atlantic Ocean below, grateful to my family for having roots in this part of the world.

My maternal grandfather had been a successful serralheiro. As a blacksmith he did well until that business began to disappear with the replacement of the car. His son, heir to the business, made bad investment choices, so my uncle and his family left for Fall River, USA.

I don’t know what would my life had been like had my parents not immigrated to Canada. But I think I can safely say that all the opportunities afforded me in Canada, would not have been matched by the social conditions of the time back in the Azores.

I’m in touch with young relatives who still live on the island and they tell me of the struggles and challenges they face; lack of job opportunities and the high cost of buying a house are some of the reasons they might even dream of leaving. But if they leave now, where can they go with assurance of a better economic life during such an unstable time, everywhere?

For several years, my mother helped out a young family in São Miguel who live in Feteiras with money which she and a group of her elderly friends send every month. This family simply can’t make ends meet. The husband is unemployed, has a work disability that went uncompensated for, the children have multiple health issues, and their own families are not in a position to help them financially. But the funds my mother and her friends provided are not sustainable as a means to keep this young family solvent.

Doesn’t the local government care? I don’t know the answer to this question. I do hear a lot about local politicians celebrating the old immigrants, those who have made it across the pond, and now send money or whatever else immigrants do to repay their old country in gratitude for their success. But relying on gifts and the generosity of those people bound by feelings of nostalgia and saudade is an unsustainable and false way of meeting the needs of a people. It’s a band aid solution that keeps the poor entrenched in their poverty in the guise of well-intended charity.

My family was shocked years ago when we began to hear through the newspapers that there was a drug problem on the island. And watching the Netflix fictionalized series, Rabo de Peixe (Turn on the Tide), which tells the famous story of how drugs one day appeared on the island, and ruined a generation, was unbelievable to see. It was so strange for us to think of São Miguel as a place where the infiltration of drugs could be a reality. Young boys stealing old earthenware pots and bedroom Redomas with statues of Saints from their neighbours to sell to antique dealers in the city to support a drug habit. A documentary of the real events of 2001 will be available soon on Netflix.

A recent book by Rúben Pacheco Correia, Rabo de Peixe: Toda a verdade, tries to restore dignity to the people of Rabo de Peixe who have lived with the stigma of this sad situation for so many years.

Yet, we also knew the trouble of drugs here in Toronto. Many families had at least one offspring addicted to something. But there was vergonha in everyone’s mind and out of shame, no one was willing to admit to, or face head on, issues of drug addiction and family violence in all its ugly permutations.

That things were going from bad to worse was unthinkable to those of us now living so far away from the Azores. Not that Canada was or is free of its own ugly truths about poverty, drug addiction, and family violence. I remember the shock I once felt while visiting Vancouver, turning the corner of a street and seeing a multitude of the unwanted of society on the other side. I simply turned back and walked again on the pretty, safe streets of the city.

And I suppose that’s what is done everywhere: a turning of our backs, a quick refresh of the Instagram page will keep assuring us that our lives are good, that there is only beauty in the world; that it’s better to see that beauty and walk away from what is also the ugly, disturbing, and wretched other side of all the tourism slogans, be them to champion the small Azorean islands or the big cities of the world.

There are now food banks near my upscale neighbourhood and I see huge line ups of people, many who no longer fit the stereotype of the down and out. Since the pandemic, many have lost their jobs and haven’t regained them. They, too, need to eat, but the price of food in Toronto keeps going higher, as does everything else. Are there any Portuguese people in those lines? I don’t know. What we do focus on is mostly on those things that will build us up as an ethnic group: the success of mobility into the suburbs, economic stability, a mortgage free home, money in the bank. The truth is that Azorean immigrants brought with them a strong work ethic, and for the most part contributed to the building of cities like Toronto. There is no reason not to feel proud of “us” as a group. But there will always be those who remain disadvantaged for all kinds of reasons.

Poverty and homelessness are not unique to one place but have become a shared global phenomenon. But it’s always particularly shocking when it occurs close to home. It’s when we start to pay attention even if we don’t do anything about it.

It pains me to look at the uncomfortable truth that many people who live in the Azores, our little bit of paradise, as one of my cousins refers to our home in São Miguel, struggle to make ends meet while all this beauty around them is being celebrated by the government and the tourist. I have no solutions to offer. What I have tried to do here is provide a snapshot of my family’s journey of immigration with economic necessity as a motivating fact for leaving to new lands. Sixty years later, my cousins’ children are doing fine. All this built on the foundation of our parents’ and their decision to leave the Azores, a place we still continue to look back to, never really breaking away from it.

Jénifer, the young girl in Joel Neto’s narrative, represents so many of those who, like her, wish for the title of Princess of France; or some other mythical, hopeful title that stands for security, shelter, food, the good life. I hope that all the Jénifers who live constrained by poverty find their France in these unknown islands.

The Portuguese version is an excellent read.

A good review written by Aníbal C. Pires.

Achada, São Miguel, Açores

Achada, São Miguel, Açores

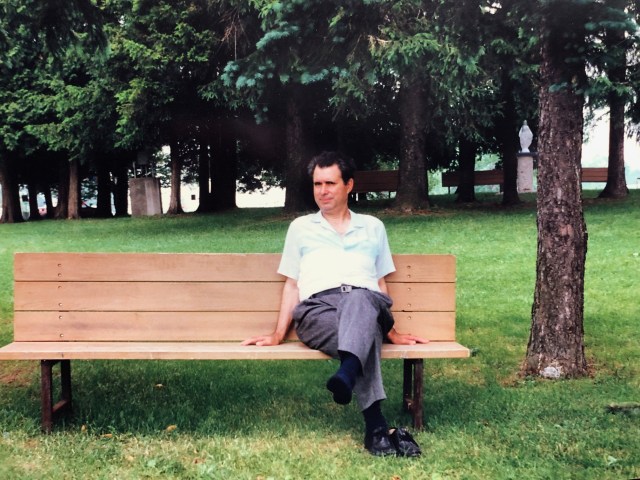

My father, Antonio Cabral de Melo at Mary Lake, June 17, 1990

My father, Antonio Cabral de Melo at Mary Lake, June 17, 1990

Photos taken on a pleasant day in October, 2012.

Photos taken on a pleasant day in October, 2012.